My brother died two weeks ago. I keep looking at that sentence, thinking, “That’s a shocking thing to say; it feels sensationalist. Do I want to be sensationalist?” But it’s just true.

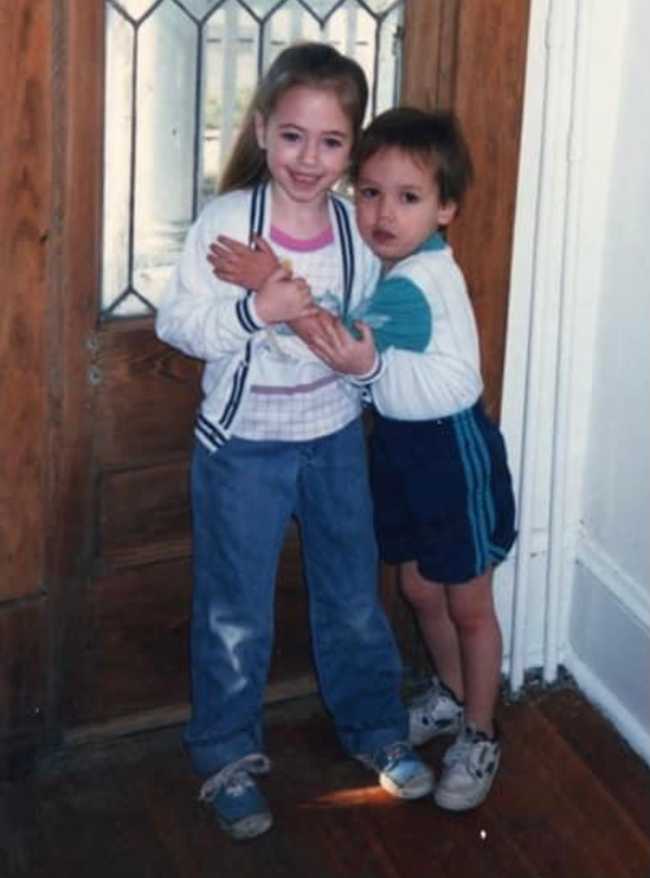

He didn’t die of what I thought he would die of—he had Type 1 diabetes that was hard to keep under control. Throughout my life I’ve often imagined his funeral to prepare myself, just in case. I especially imagined the photo reel of his life being shot onto one of those church projector screens with the nostalgic music playing and everyone crying. I knew him best when he was a sweet-cheeked little kid who never knew a stranger and often had his hands in peanut butter jars, so I picture that. I also picture me trying to keep his grubby three-year-old hands away from my brand new talking Mickey Mouse with those white, white gloves.

But diabetes didn’t end up being the culprit. Instead, he died of a brain aneurysm that no one could see, prepare for, or expect. He was 36 years old, two years younger than me, the same age my mother’s mother died when my mom was just a child. She died of Type 1 diabetes, so my brother was relieved and proud of himself for making it that far.

Grief is piercing and strange. I’ve experienced it in small ways, like most of us have, but never this kind. My brother and I weren’t close as adults—too much baggage from growing up. I don’t know if grief takes that into account when you lose someone in your family. Maybe it doesn’t, or maybe it makes it worse. I don’t have much to compare it to.

When I heard he wasn’t going to come out of the searing-headache-turned-seizure-turned-coma, I gasped and wailed and heaved like I’d lost my firstborn. After several days of on-and-off crying jags, followed by stretches of benumbed staring at the ceiling, I was able to fly back to Virginia to be with my mom. It has been so, so healing to grieve together. Having lost her mom at such a young age and having experienced many losses since, she is the wisest griever I know.

“You have to let it out,” she says. “Don’t hold anything in, not a thing. Feel all of it.” She tells me stories about him all day, about how he loved Iron Man and telling jokes and how he wanted to work with dialysis patients once he got his hoped-for kidney. He rarely left a place without telling everyone there that he loved them because he didn’t take his life for granted. I tell her about how we used to pretend our beanbag chairs were giant mustard and ketchup bottles that we’d drive around the living room. I tell her how we danced to the lime in the coconut song, how I remember him bare-skinned except for his diaper and cowboy hat, sugar free pudding smeared all over his face.

When I went to see him in the hospital one last time, she told me I could hold his hand, and she warned me against trying to keep my crying under control. “Let it out. Let it out. Let it out.” My husband encouraged me to talk to him, even if he didn’t have any brain activity left. “You can tell him anything, Sarah.” And when I couldn’t say anything except “I love you” over and over, he held my hand and prayed the rest.

It must be so hard to process grief alone. My dad went to Africa, and he hasn’t been able to get back yet because of lockdown. It’s very hard for him, being there alone, waiting to get the go-ahead to come home. I think of all the people who have lost loved ones to COVID and not-COVID this past year, and who have had to experience solitary grief. I don’t think we were designed for it. I wonder at how much is left unprocessed until we can share it with another, and it makes me want to fix that for the whole world.

But when we can process our grief, fully and collectively, it can be beautifully healing. It’s like our bodies know how to heal themselves, not just in knitting together broken bones, but also broken hearts. I wouldn’t have believed that in the beginning. But after spending this time with my mother, and watching the way she grieves, so fully and even joyfully, I’m starting to believe it now.

Which makes me wonder at all the things I do to avoid loss, to avoid grief. I worry what will happen if I fail at my job, what will happen if my partner and I grow apart, what will happen if I haven’t prepared my kids well enough for the world they find themselves in. I worry about people on the Internet and living up to my potential and whether I’ve been too ambitious in my grocery shopping and maybe things are starting to rot in the fridge. I build all kinds of little hedges around myself to protect me from anything I’m afraid of losing.

Fear is a lot of work. So is grief, but at least there is healing on the other side.

Grief is still surprising to me. Even now as I’m writing this, I’m thinking, “I’m okay now. I’m definitely okay.” I mean, I’m writing something I might even share, which I couldn’t have imagined a week ago. Tomorrow I might be sobbing again and thinking how am I going to do anything except for hug my family ever again. As much as I used to think I knew myself, grief has taught me this isn’t completely true. Our hearts are such strangers when something we love is taken away. We never know where the unalterable truth will hit us.

It might sound morbid, not to mention impossible and inadvisable, but I’ve been tempted to think it would be better to grieve everything in my life now, before it’s gone. I could grieve my relationships, my job, my identity even. I could let this go and that go…let everything go. Let the loss of it completely overtake me, hopefully without breaking me. And then when I’m done, let myself experience everything, not as if it were mine to hold onto, but as if it were a gift. I could walk back into the world as if I’d just been born, and owned nothing. Then maybe I could learn to appreciate all of it while it’s here.

But of course that’s not how it works. We can’t grieve things that aren’t gone. Fear of loss is its own thing; we don’t get to choose to preemptively grieve instead. And hope, as beautiful as it is, interrupts any grieving that might aid us in our healing. There is a push/pull to it that keeps us hanging on. Perhaps this is why, as Breai Mason-Campbell writes, “Situational grief is momentary. Systemic grief is not.” We can’t grieve what isn’t gone, or what keeps getting taken away.

The best I can do in this moment is to remember the temporary nature of all things, and to use that to appreciate that we get to be here, together, right now. Grief and gratitude strike me as the closest of siblings.

Goodbye, little brother. I miss you so much.